HOW SHE MOVED

Archaeological Museum of Paphos District, 2024

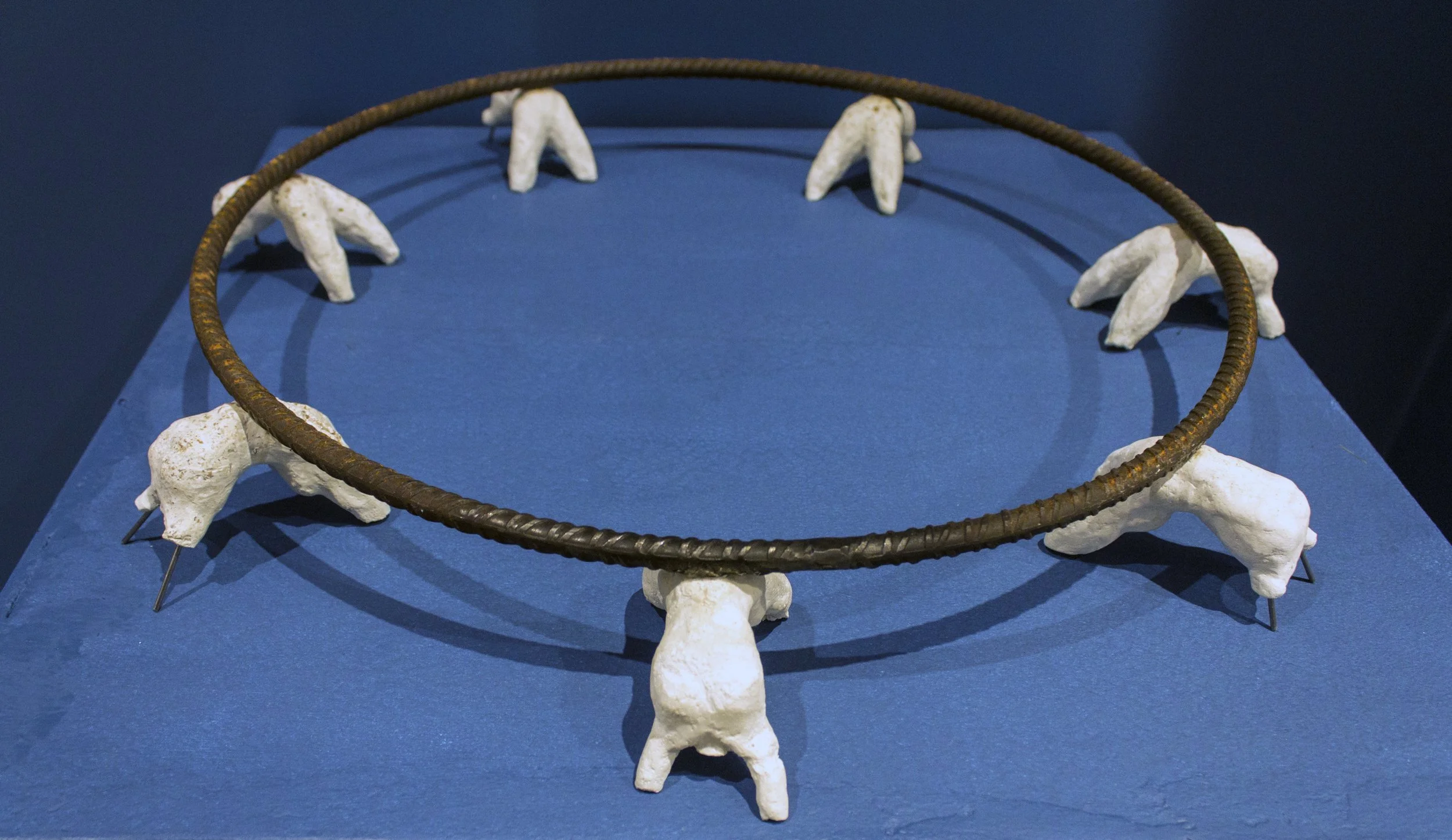

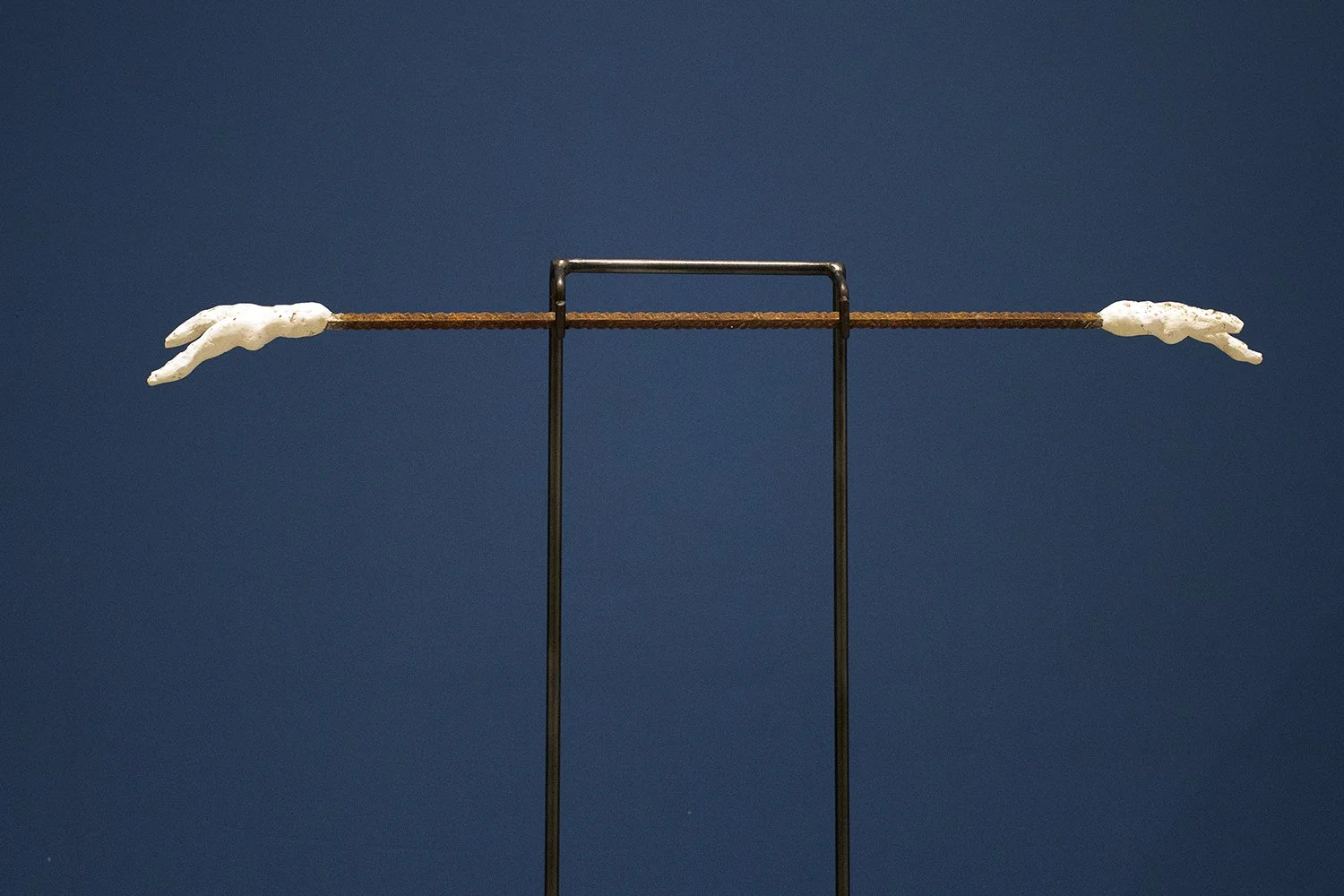

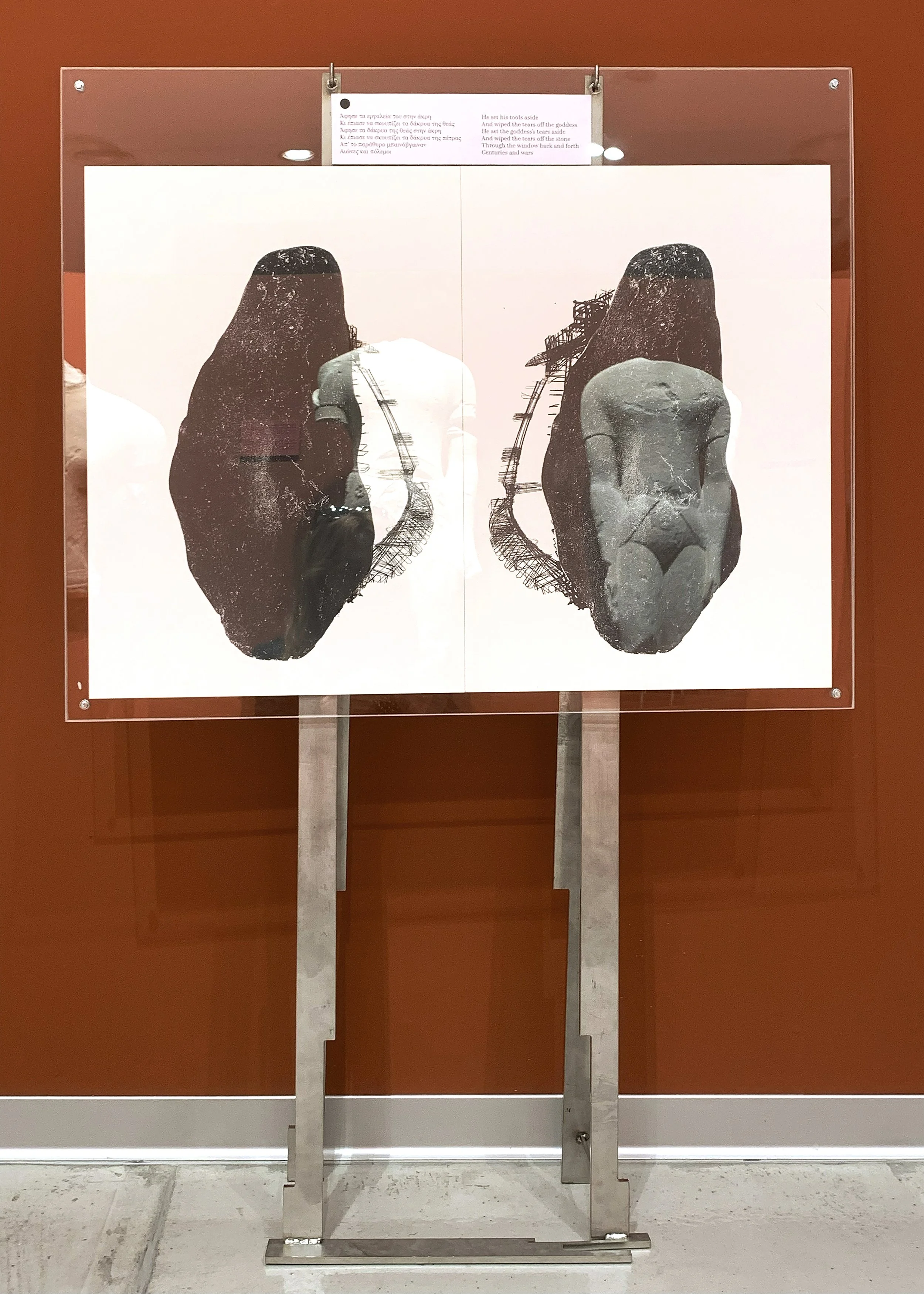

Marble dust, sea shells, white concrete, rebars, silkscreen prints, stainless steel, plexiglass, poetry

dimensions: variable

How She Moved is a sculptural and silkscreen print-based installation that exposes how architectural tension, aesthetic fatigue and ideological systems, pollute and mutate, not only our bodies and the environments we inhabit, but also the very stories we live by. In an age where myths no longer anchor identity, the work aims to reveal the intimate cost of contemporary systemic strain, by cutting a cross-section through past and present narratives, revealing the new stories about the mutated mythology of a Goddess.

The research focuses on the ancient Great Goddess of Cyprus and explores the perception and representation of her body through an archaeological lens. Further more it investigates the ways in which her mythology connects to and is transformed by the contemporary era. In Paphos she is originally depicted as a conical black Baetylus, and in the Hellenistic period was worshipped as Aphrodite when she was identified with the goddess of Greek mythology. Her sanctuary at Palaepaphos was a center of wealth and power, a crossroad of copper routes from Troodos Mountains, giving the goddess a geopolitical identity. Under colonial regimes, the goddess and the land, were transformed and increasingly exploited. Today, Aphrodite remains a charged metaphor for Cyprus itself: a landscape continually carved, extracted, built upon, and sold in the name of development, an island which bears the scars of ideology, capital and architecture.

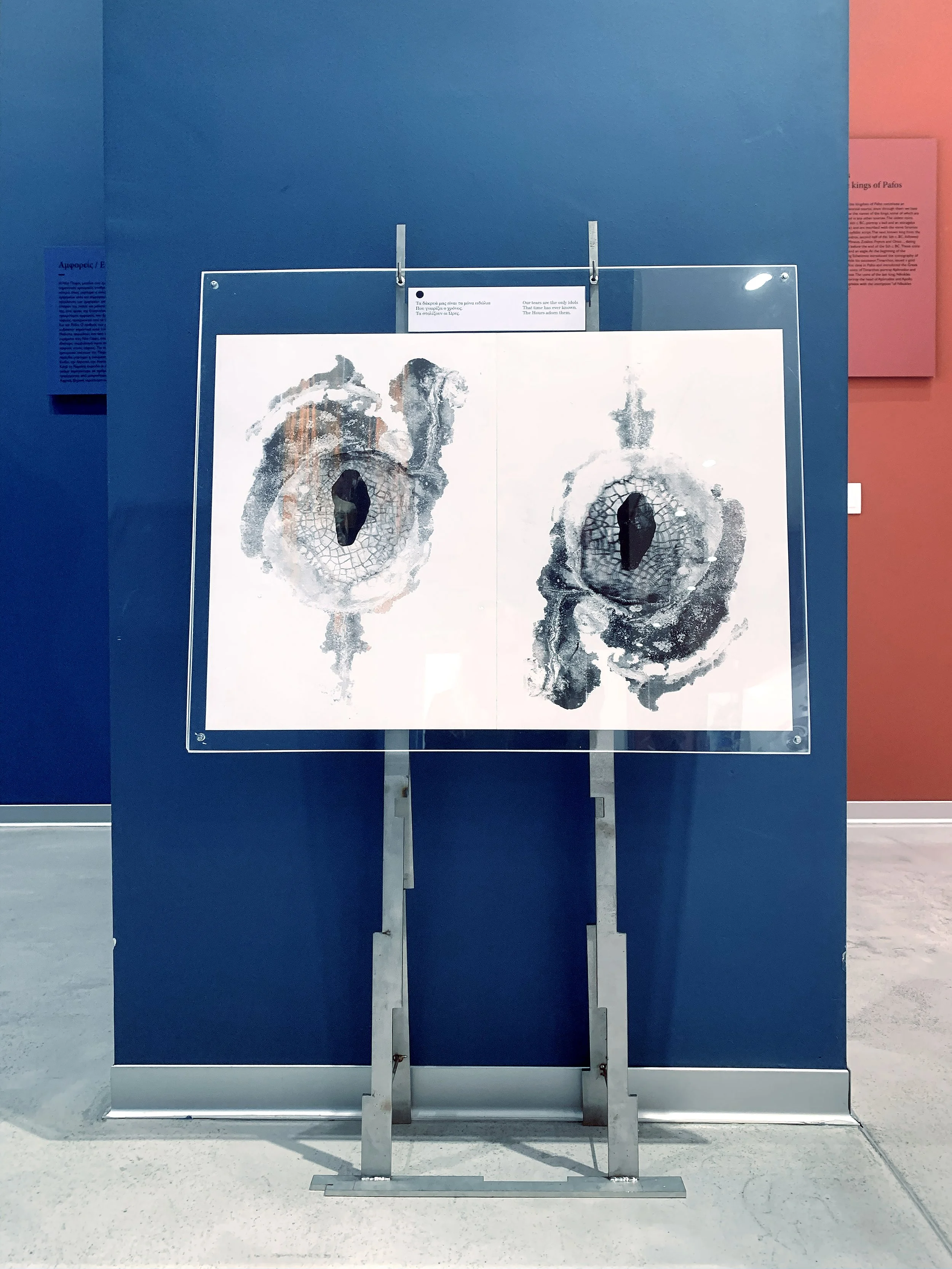

According to Elizabeth Grosz’s spatial philosophy, architecture here is not a backdrop, but a force that actively produces tensions and distortions in external and internal terrains alike. These tensions are deliberately internalized by the artist through a daily ritual that draws from her psychoanalytic imagery and psychosomatic practices. This naïve attempt to restore balance systematically fails—instead, it produces a visual language of the peculiar contemporary mythology, first rendered in silkscreen compositions, then in sculptural forms.

The silkscreens depict Aphrodite’s baetylus burdened with fragments of dysfunctional architecture -rebars, scaffolding, and jumping boards- as well as falling in the void bodies. The sculptures, constructed from concrete, marble dust, tar, shells, and metal rebars, form figures balancing under infrastructural weights. Neither monuments nor ruins, these forms evoke both sacred relics and industrial debris, translating internal states into form.

The installation at the Archaeological Museum of Paphos District sits in dialogue with ancient artefacts spanning from the Neolithic to the Hellenistic eras of Cyprus, when the Great Goddess was worshipped. The archeological exhibits provide a continuum and yet, a contrast also, to the anatomies of How She Moved, opening a transhistorical reflection on embodiment, myth, and material memory, tracing the mythopolitical journey from primal goddess to colonial deity, from copper mining to psychic excavation, from sacred form to commodified body.

This islands myths are re-examined not as static heritage, but as living matter—malleable, vulnerable, and continually reshaped by contemporaneity.

The Great Goddess transformed over time, manifesting her divinity in various ways.Her countless names, her multiple forms, continue to inspire to this day.

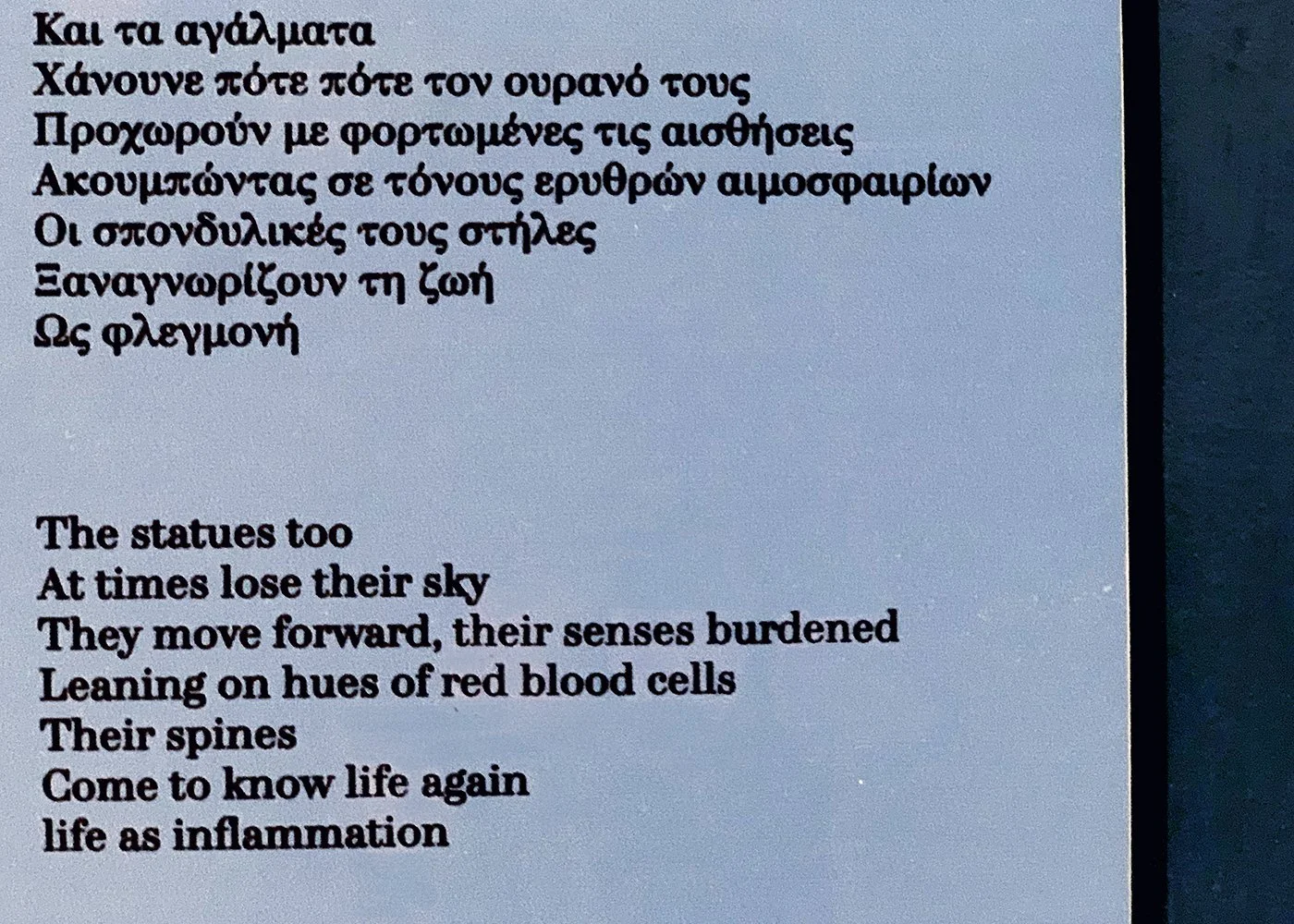

The poet imagines and contemplates:

A celebration for the body of Aphrodite. A celebration for the body. Who imagined this celebration? Who heard the instruments play,

the stones speak? Some will say they saw the photographs. Some will say they found the manuscripts. And others will swear that nothing was found, except a kaleidoscope. Colors. Shapes. Fragments. Tears. A great serpent, embalmed. Adam’s apple. Polyps in a silver womb. And flowers upon the polyps. Roses, myrtle, shells. The genderless little body of a moment.

The myth. All mixed together with the sacred fluids of love. And behind them: The sacred fluids of love. The myth. The genderless little body of a moment. Polyps in a silver womb. And flowers upon the polyps. Roses, myrtle, shells. Adam’s apple. A great serpent, embalmed. Tears. Fragments. Shapes. Colors. Like those gathered by the sculptor in a moment of boredom, walking down the path from Palaipaphos to the highway— highway to heaven for anyone who managed to keep their gaze steady upon theeternal sculpture of the sea.

And those who couldn’t? They will murmur all night long that their own tear looked uncannily like the tear of the stone. The tear of the stone before it became body. Or rather, when the stone was the body and no one held a measuring tape, counting how many carats of love could fit in the thighs and the breast (what an obscene patron, truly, Western civilization, lounging among the statues, reading the sports section and advertisements, forever weighing the odds before placing an exorbitant bet on some exorbitant gamble…) Please, ask for the patience of the tourists on the bus. The stones are praying. Please, remain in your seats a little longer.

The stones. The stones are sleeping. The stones are dreaming. Do not step on the tears. Do not disturb the sculptor. As he lays out his tools to change the bandages, to heal the wounds, to soothe the impossible transformation of the goddess, and to speak of the incurable dreams of statues. Please, remain in your seats a little longer, as we take a few notes on the sculptor’s work:

He set his tools aside

And wiped the tears off the goddess

He set the goddess’s tears aside

And wiped away the tears of the stone

Through the window passed

Ages and wars

The tears of stone and goddess will often be heard, the tears of statues. The gasps from the dense back-and-forth between East and West. [The scene is interrupted by a nightmare: The sculptor, hands bound behind back.] Stories will be heard—some widening the road, others falling like spotlights on that little path descending from Palaipaphos. The touches of Katerina and Grace will be heard, struggling to tend to every truth left untended. Nursing those dreams lost in the near-impossible crack between two betting slips. From the kaleidoscope, names will overflow—mosaics of Aphrodite, drops of the goddess’s eternal sweat. Drops of the eternal sweat of stone:Kypris, Paphia, Kytheria. Aphrogeneia, Thalassia, Euploia, Pelagia, Navarchis. Pandemos, Ourania, Kallipygos, Androphonos. Akraia, Anadyomeni. Drops of the eternal sweat of truth. Scotia, Cthonia, Peitho, Xeni. I keep looking at her until I, too, become a stranger, until I find the space to embrace my own estrangement. To welcome the transformations. To step back into the temple, leaving my dreadful mist outside. Please, remain in your seats a little longer. Countless speeds rush past us.

The statues of day and night running clumsily across the centuries.

I pause for a moment. I converse with the dust on the statues. The dust on the gods. The dust on the myths.

At the edge—

the small body of a moment.

Sacred is the little voice of every moment,

Her tender statue.

poetry by Stella Voskaridou